THE MAIDS

by Jean Genet

new version written and directed by Kip Williams

Donmar Warehouse, London – until 29 November 2025

running time: 100 minutes no interval

https://www.donmarwarehouse.com/whats-on/the-maids-fs5q

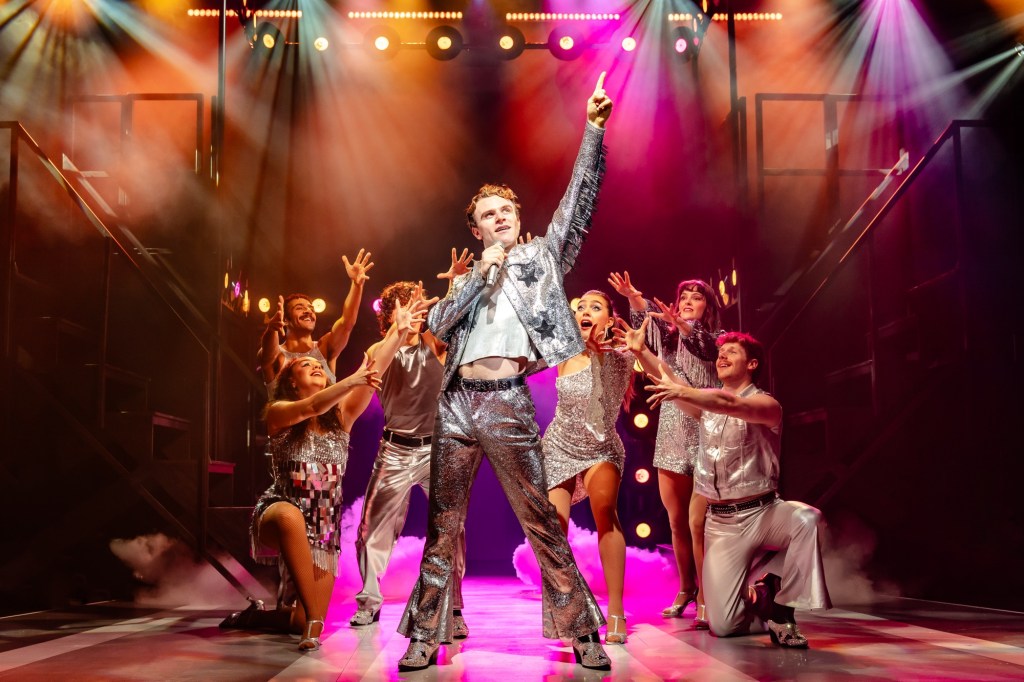

Swapping the narcissism and cruelty of Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray for the shadowy same-sex erotica and claustrophobic power games, but also cruelty, of Jean Genet’s esoteric 1947 three hander seems like a natural progression for Australian auteur Kip Williams. If The Maids, reinvented for the social media generation, feels like a sequel to the recent The Picture of Dorian Gray in terms of bravura performances, slightly hysterical tone and, especially, in the use of visually astounding, groundbreaking tech, it’s a striking piece of theatre nonetheless.

Allegedly inspired by an infamous real crime where a pair of sisters murdered their employer in 1933 France, the original Genet is more stream-of-consciousness fever dream than coherent drama. The previous Donmar production in 1997 directed by John Crowley rendered it fey and esoteric, while a starry Jamie Lloyd revival at Trafalgar Studios nearly a decade ago was flashy but still mystifying. Here it remains ritualistic and periodically ponderous, but informed and enlivened by the ultra modern approach. The themes of self-loathing, envy and repressed longings are a marriage made in heaven (or hell?) with the self-obsession and mutual ownership often engendered by social media use: a frequently impenetrable play is illuminated (literally and figuratively) and made wildly entertaining.

In fact, Williams is only collaborating with one of his Dorian Gray creative colleagues here, costume designer Marg Horwell whose eye-popping art-meets-fashion creations for Madame – usually a socialite but here an image-obsessed online influencer – could teach the team over at The Devil Wears Prada a thing or two. The aesthetic is similar to the earlier show though, with actors features cartoonishly beautified or grotesquely modified via filters as their images are live-streamed up on the the vast mirrored screens dominating Rosanna Vize’s opulent, oppressive boudoir set.

Lydia Wilson and Phia Saban as ladys maids Claire and Solange, the role-playing sisters under the thumb of the histrionic Madame while plotting her demise and wishing for different existences, are haunting and impressive, alive to every change in pitch and emphasis in Williams’ new text which is going for essence of Genet rather than slavish adaptation. There are references to social media apps, vaping, Soho House, contemporary fashion designers, and so on ….the language is snappy, dirty, terse, and often extremely funny.

The contrast between the heightened grandeur of Claire pretending to be Madame and her self-effacing throwaway delivery as her way less confident self is superbly managed by Wilson, whose combination of stridency and vulnerability tantalisingly suggests what a great performance her Blanche DuBois might have been in the Almeida-Paul Mescal Streetcar. Saban is every bit her equal, giving Solange a pragmatism and eagerness that is extremely affecting, the epitome of a young woman who constantly feels that she’s in the shadow of others.

Probably the longest shadow is that cast by Madame, a gorgeous monster in designer gear, played with spitfire precision and comic volatility by Yerin Ha. She’s a merciless parody of the new-ish breed of physically blessed, self-aggrandising young person rich and famous for reasons that nobody can quite fathom; a ghastly human being perhaps but, as presented and played here, fabulous theatrical company. It’s not hard to see why she fascinates the sisters so much, but it’s equally clear why they feel compelled to destroy her, in a fitting metaphor for the para social obsessions that are the downside of fandom and constant access via modern mass media.

The garish artificial beauty of the world these women exist in belies the ugliness and banality lurking beneath; Williams and team capture this with a vicious brilliance that unsettles as it simultaneously delights. Zakk Hein’s video designs and the music score by DJ Walde, redolent of club beats then grand opera, are essential components in the shows success.

It’s a provocative reflection on our modern obsession with bright, shiny things….and Williams’ dazzling production is a very bright and shiny thing. It’s also lethal. Whether you find it exhilarating or simply exhausting will depend on your tolerance for all the posturing and digital trickery, and how much you can engage with the humanity of the deeply unhappy sisters. Personally, I found it unforgettable.