MRS WARREN’S PROFESSION

by George Bernard Shaw

directed by Dominic Cooke

Garrick Theatre, London – until 16 August 2025

running time: 1 hour 45 minutes no interval

https://nimaxtheatres.com/shows/mrs-warrens-profession/

Imelda Staunton and her daughter Bessie Carter make a formidable pairing in this bracing revival of the George Bernard Shaw classic that pits respectable, genteel, highly educated Vivie Warren against her wealthy, brash and frequently absent mother Kitty. Their already fraught relationship is put under immense strain when Vivie realises her mother’s fortune derives from prostitution, and is then fully shattered when it emerges that the “family business” is an ongoing concern and not a temporary solution to the poverty that Kitty was born into.

These aren’t spoilers – Mrs Warren’s Profession has been around since 1893 although director Dominic Cooke sets his streamlined, interval-free staging in 1913, just before the First World War. I’m not sure what the difference in decade really alters as the tension between culpability and living with the knowledge that one’s privileged existence is on the back of those less fortunate is a timeless one, as it proves once again here.

Like the text, the production is pared back. Designer Chloe Lamford has created an austerely beautiful space, a rotating disc initially redolent of a floral garden but one that gradually gets stripped of its accoutrements (the furniture, the grass, the flowers themselves) much as Vivie’s illusions about her upbringing and provenance are worn away one by one in the course of the play. The supernumeries who transform the set are a group of women clad in old fashioned underwear, presumably the victims of Mrs Warren’s ambition and thirst for money. They also observe much of the action from the sidelines, haunting, haunted figures, some accusing, some almost pleading. Stephen Daldry did something similar with his silent chorus in the career-redefining An Inspector Calls. As a directorial flourish, it’s pretty on-the-nose but it’s undeniably effective.

By the final scene, Lamford’s set has been transformed one last time into a stark circular office, one where Vivie and her business partner are now ensconced near Chancery Lane. There’s just a desk, a door and a vast expanse of grey. It serves as a usefully gladiatorial space for the final, thrilling showdown between mother and daughter but it also feels like a prison cell, no more so than in the very final moments where an emotionally spent Vivie sits in silence being watched balefully by the phantom women who, one suspects, will never fully leave her even though she has jettisoned the mother who turned them into sex workers.

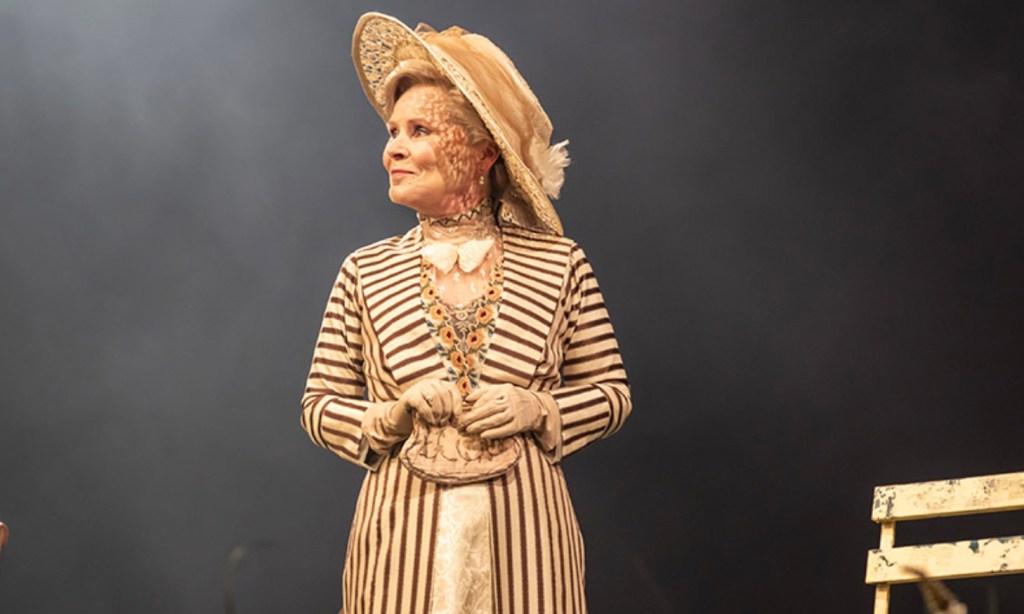

Lamford has created some wonderful costumes for Staunton, quite beautiful and just teetering on the edge of being a bit much (“can you imagine me in a cathedral city?!” cries Kitty at one point). Jon Clark’s lighting and Angus Macrae’s soulful, if slightly over-used, music complement Lamford’s designs. It’s a muted but handsome production.

Staunton is a fascinating Kitty Warren. She plays her very much as the self-described vulgarian, with a sharp, watchful energy, broad working class London accent and a veneer of impenetrable toughness. Just how hard is that shell though? When she breaks down at the end, it’s ambiguous: is she play-acting or is she genuinely heartbroken? It’s not clear but it’s all the more compelling for that. This Mrs Warren seems more confident dealing with the men than with her own daughter. She’s part drama queen, part tough cookie, but entirely human. This is a superb performance; if it doesn’t really surprise, that’s probably due to a general expectation that Staunton is always going to be excellent.

Carter’s Vivie, all cut glass accent and nervous energy tempered with a fierce intelligence, is another fine creation, even though she, and a couple of the supporting actors, have been distractingly directed to deliver a lot of their lines out into the audience rather than to each other. I’m not sure if that’s because of an awareness that the playing area is slightly too far upstage to really engage a lot of the audience, but I suspect Shaw doesn’t actually need the help. Still, Carter judges with real skill the journey from benign self-assurance to appalled anguish though. When the two women go head-to-head the play becomes truly engrossing, probably enhanced by the knowledge of their real life relationship, even though their characters and consequently their performances are very different: Staunton is all fire, earth and stone, while Carter is elegant and witty, but both are united in an undertow of sadness.

All of the male roles are played pretty broadly but Robert Glenister finds a horrible, gruff power in amoral Sir George Croft, Kitty’s business partner with designs on Vivie. Reuben Joseph is a hugely likeable breath of fresh air, tinged with a certain louche languor, as the much younger man who could theoretically be a much better match for the younger Warren bar one distressing revelation.

The weighty erudition of Shaw’s language remains a pleasure, as is his astonishingly forward-thinking understanding of the limited lot of women at the time of writing. The theme of exploitation of other humans in order to achieve the lifestyle and status one aspires to, is as relevant today as it was at the end of the nineteenth century. Wordy, worthy but engaging, Mrs Warren’s Profession may not be a particularly dynamic drama, but it remains a potent one.

Leave a comment