KING LEAR

by William Shakespeare

directed by Yaël Farber

Almeida Theatre, London – until 30 March 2024

https://almeida.co.uk/whats-on/king-lear/

Shakespeare’s bleakest tragedy gets a haunting, multicultural makeover in South African director Yaël Farber’s uncompromising yet ethereal new production for the Almeida. As with her James McArdle-Saorsie Ronan Macbeth at this venue in 2021, Farber isn’t afraid of a lengthy duration, and this Lear clocks in at the full three and a half hours. But similarly to that iteration of The Scottish Play, the running time feels necessary to build the shuddering suspense and tense, forbidding atmosphere. There is a current of electricity, aurally actualised by Max Perryment’s omnipresent thrum of piano and violin music, running throughout the entire performance that ensures a long evening is a consistently engrossing one.

Farber and her designers Merle Hensel (set), Camilla Dely (costumes), and Lee Curran (lighting) have created a strikingly dark world for the play where the trappings of sophisticated living (spirits are gulped from expensive-looking glass as a singsong happens around an upright piano, Regan appears in silk pajamas, a Habitat style floor lamp illuminates the blinding of Gloucester) exist right next to scatterings of muddy earth, the skeleton head of an impala, and lots and lots of blood. It has the classic hallmarks of a Farber production: earthy, elemental, touched by her native Africa though not necessarily set there.

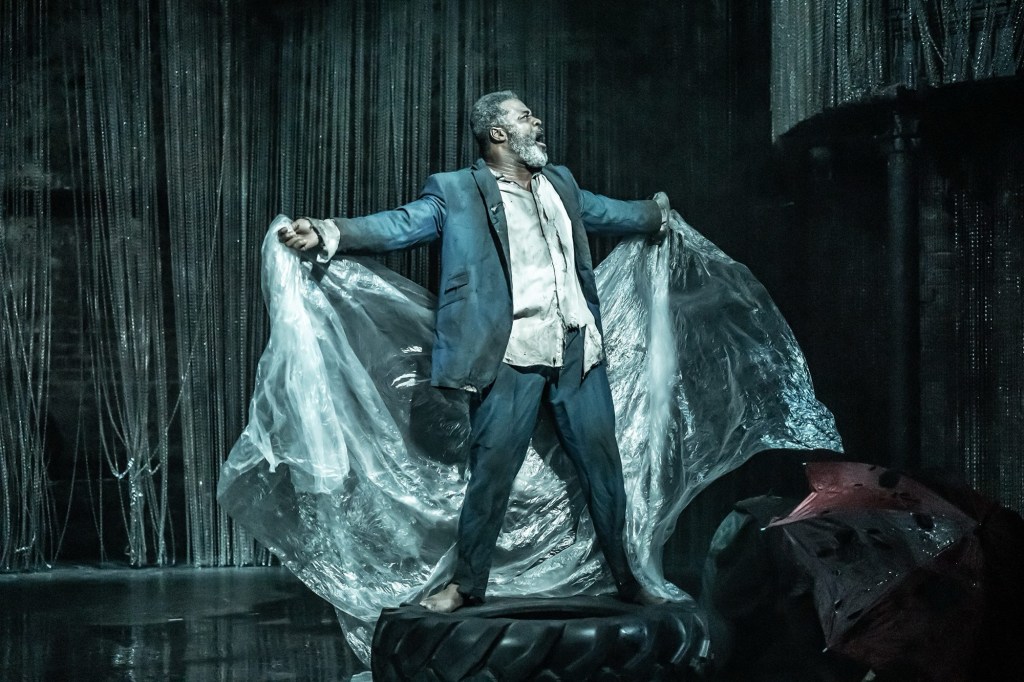

Although the time and place is unspecified, the collective visual clues are potent and familiar: Danny Sapani’s Lear first comes on like some tinpot military dictator bellowing into a microphone in his powder blue suit; when he and Gloria Obianyo’s Cordelia are captured, the sacks over their heads and the grimy boiler suits recall the prisoners at Abu Ghraib. ‘Poor Tom’’s dwelling is reminiscent of the tent cities that seemingly spring up under every railway arch in major cities, and there’s the terror of modern warfare in the deafening explosions and overheard whirring of helicopters in the battle scenes. The sound design by Peter Rice is unsettling and highly effective throughout. Also worth a mention is the fight direction by Kate Waters which feels dangerous and desperate.

The performances are all strong, and in some cases revelatory. The downfall of this Lear is less to do with age than collapsing mental health. In the first scene he is frighteningly unpredictable, his violent rage at what he perceives Cordelia’s public betrayal comes out of nowhere although it feels entirely organic, and the body language of his three daughters suggests a lifetime of verbal abuse and bullying. Sapani’s bullish, dynamic King seems to know that he is only one setback away from completely losing the plot, and the way he hits the line “o fool I shall go mad” as he exits after a final showdown with his two older daughters isn’t a cry of despair so much as a statement of resignation, as though he always knew this moment would come. When fully mentally untethered, this Lear becomes bitterly funny, and while it’s not a sympathetic reading of the role, it’s a memorable one. You can’t take your eyes off him, nor off his Fool, whom molasses-voiced Clarke Peters turns into a knowing, elegant, magnetic truth teller, more regal than the actual King.

Obinayo’s equally unconventional Cordelia might be a chip off the old block. About as far removed from the cosseted princess she’s often portrayed as, she’s a contained young woman who becomes an alarmingly aggressive soldier. The contrast between her and Akiya Henry and Faith Omole as Goneril and Regan is huge. A side effect of such a volatile Lear is that it humanises the “bad” daughters, at least at first. The way Henry’s tiny, glamorous older sister recoils from Lear’s fury is painful to watch, and when she cradles her sisters (Cordelia when she’s rejected, and Regan when she’s dying) she suggests a warmth and humanity that is allowed to curdle. Regan appears similarly traumatised (the way Lear awkwardly forces this grown woman on to his knee then refuses to let her go even as he rages, is plain horrible) but the blinding of Gloucester (appropriately distressing, and skilfully managed) seems to unleash something in her. Omole makes chillingly credible the transformation from beautiful marionette to snarling panther.

Fra Fee’s sexually irresponsible, hipsterish, Ulster-accented Edmund, resembling Game of Thrones-era Kit Harington, is simultaneously louche and fierce, as ruthless as he’s charming. Opposite him, his half brother Edgar might initially seem a bit colourless, but Matthew Tennyson turns him into a wraith with a welter of open-hearted compassion, and the scenes between ‘Poor Tom’ and the newly blinded Gloucester (Michael Gould, excellent) have seldom been so moving. Hugo Bolton is a hilariously prissy Oswald, and Alec Newman’s staunch Kent also makes a strong impression, convincingly moving from flinty toughness to emotionally broken by the play’s shattering conclusion.

It’s often starkly stunning to look at, the overriding visual image being of figures materialising out of the gloom into pools of murky light, their faces often hard to make out. as befits a world where people’s motivations and allegiances are never fully known and can be subject to change in the blink of an eye. The infamous storm scene is brilliantly done with booming sound effects, and billowing and shaking of the chain mail strands that run the height and length of the set, it’s authentically frightening, and definitely not an environment into which any normal person would release an unprotected aged parent.

This is one probably the most compulsive reading of this brutal play that I’ve ever seen. It’s raw, sexy, shocking and leaves you with the taste of blood and earth in your mouth. It feels modern but not in a gimmicky way and never at the expense of the poetry or the story. Tremendous and troubling.

Leave a comment