BLOOD WEDDING

by Barney Norris, after Lorca

directed by Tricia Thorns

Omnibus Theatre, London – until 24 May 2025

running time: 2 hours, 15 minutes including interval

https://www.omnibus-clapham.org/blood-wedding-2/

Barney Norris’s modern take on Blood Wedding is to the original text as the recent Cate Blanchett Barbican Seagull was to Chekhov, or as the Billie Piper Young Vic Yerma a couple of years ago related to another classic Lorca tragedy. In other words, it’s a completely new play (new-ish actually, having premiered at Salisbury Playhouse just before the pandemic), and a very engaging one at that, hanging on the framework of the great Spanish tragedy. Tricia Thorns’s impeccably acted production for Two’s Company is less poetic than a faithful version of Blood Wedding but it’s also considerably more accessible and a lot more fun.

Norris transplants this tale of forbidden love and sinister foreboding to the Wiltshire countryside where he grew up, which gives a charming authenticity to the inclusion of place names and local points of interest, and makes it feel bracingly contemporary. The combination of rural British setting, working class grit and the (admittedly watered-down) otherworldliness are as reminiscent of Jez Butterworth in his Jerusalem era as it is of the second Golden Age of Spanish theatre.

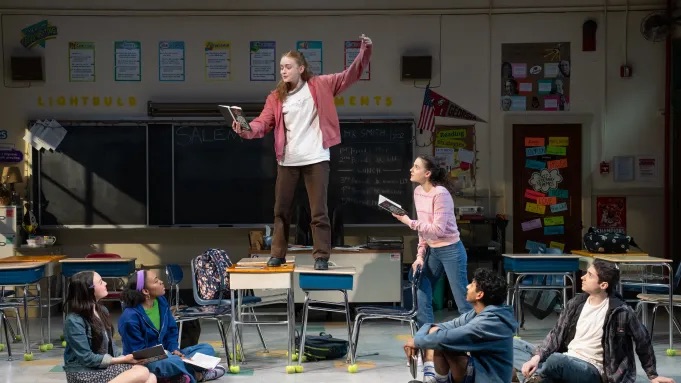

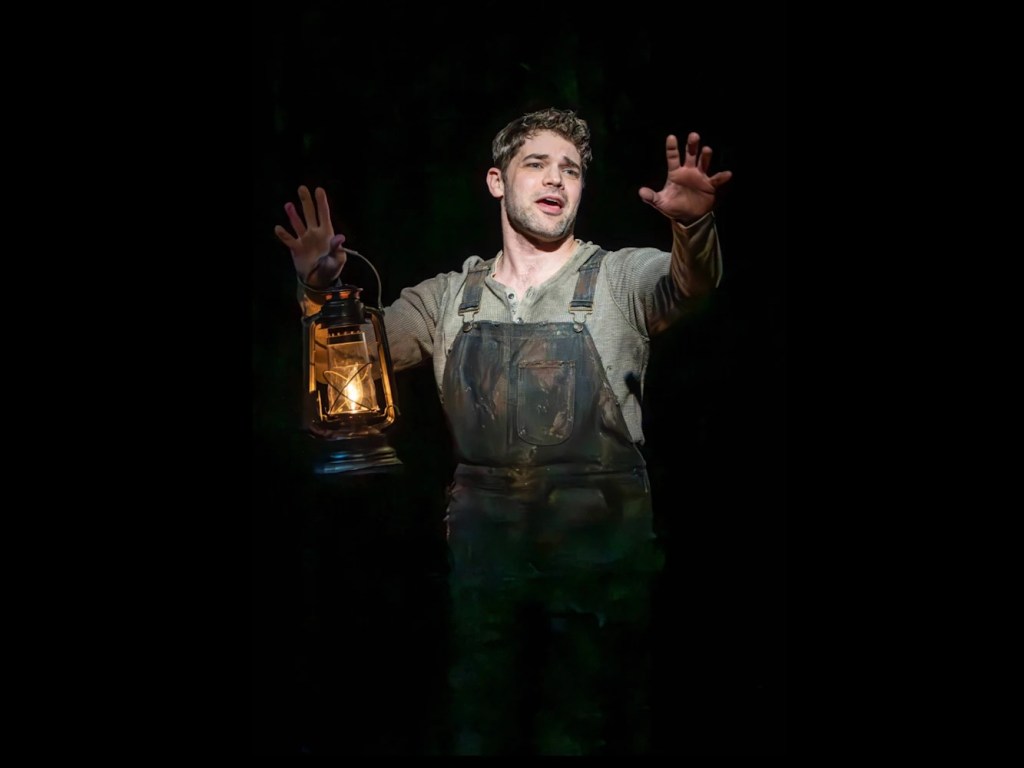

Lorca’s doomed bridegroom is now cocky school leaver Rob (Christopher Neenan), arranging his wedding to feisty, troubled, slightly older Georgie (Nell Williams) while his mum Helen (Alix Dunmore, exquisite) looks on with massive reservations. Where Lorca gave us death in human form as an old beggar woman, Norris has created loquacious Brian, the caretaker of the rickety village hall the aforementioned trio is considering for the post-wedding party, mainly because it’s so cheap. David Fielder, in a masterclass performance of utter brilliance, turns this shambling old widower into a sympathetic, slightly unnerving outsider, all-seeing and a bit needy, frequently hilarious but able to turn on the pathos at a moment’s notice.

Observing how the figures in this Blood Wedding (lurking on the sidelines there’s also Lee, Georgie’s ex, an Irish Traveller played with a perfect combination of menace and lost-boy charm by Kiefer Moriarty, who has started a family with her estranged school friend Danni, a searing Esme Lonsdale) dovetail with the Lorca adds to the fun if you’re familiar with the original but it’s not essential. Norris’s potty-mouthed tragicomedy hums along compulsively on its own terms.

There’s punchy, relatable dialogue, much of it laugh-out-loud funny, such as the way Helen’s speeches are peppered with half-baked motivational quotes as though she’s gorged on self-help manuals, and some of Brian’s lines are priceless. When Norris gets serious, he never overdoes the foreshadowing: “love doesn’t always behave well, does it?” says Danni to Georgie at one point, and it feels like a warning. It’s telling also how, every time she discusses her upcoming wedding to Rob, Georgie talks about how she ‘needs’ the stability and continuity marriage offers, but never refers to love.

The only section that doesn’t fully work, although played with spellbinding conviction by Fielder, is where Norris and Lorca most closely connect, in an extended monologue full of purple prose and poetic imagery, fusing the natural world, the mystical and the little lives of the individuals involved here. It’s not bad writing, but it feels like a clumsy gear change, present only to remind us that this enjoyable modern text has its roots elsewhere, and Alex Marker’s amateurish set has a mini transformation that verges on the laughable.

Thorns’s staging could afford to up the pace a bit and sometimes has the actors milling about aimlessly, although she makes interesting use of the auditorium as well as the stage. The performances are wonderful though. Watching Fielder feels akin to seeing one of the all-time greats but in a studio space. Williams charts Georgie’s internal conflicts with real sensitivity and passion, while Moriarty makes it entirely credible that she feels he’s bad news while also being unable to leave him fully behind. Lonsdale is vivid and moving as a young woman who on some innate level realises she’s a pawn in a game much bigger than she is. Dunmore reads as a little too young and glamorous to fully convince as a downtrodden single mum with a young adult as her son, but turns in a beautifully realised, fully rounded portrayal nonetheless, never finer than when managing a potent combination of grief and fury in the final scene.

If the first act is a comedy, act two is a tragedy, but both acts are superbly entertaining. Norris manages to honour Lorca but create something fresh, and as with the better soap operas, you can’t wait to see what happens next.