INTIMATE APPAREL

by Lynn Nottage

directed by Lynette Linton

Donmar Warehouse, London – until 9 August 2025

running time: 2 hours 25 minutes including interval

https://www.donmarwarehouse.com/whats-on/34/by-lynn-nottage/intimate-apparel

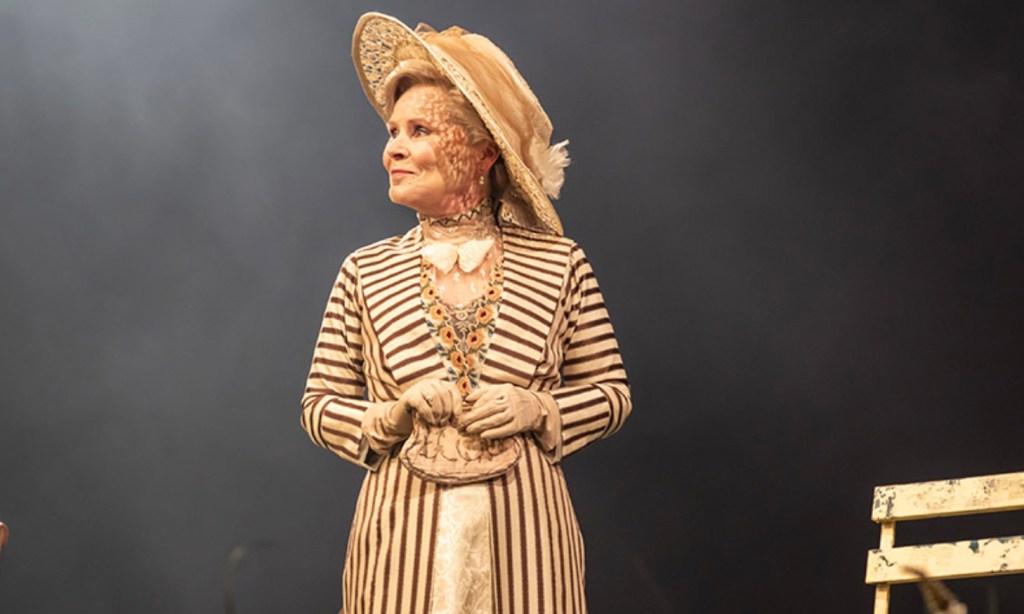

Double Pulitzer prize winner Lynn Nottage is one of the greatest living American playwrights. Her plays frequently surprise and confront, but the majority of them have a compassion, humanity and generosity of spirit in common. The earlier Donmar productions of Sweat (2018) and Clyde’s (2023) suggested that in director Lynette Linton, Nottage had found the ideal British interpreter of her work. That theory is given even further weight by Linton’s gorgeous new production of Nottage’s Intimate Apparel, a tasty, twisty story of working class Black womanhood in the New York City of the turn of the 20th century.

Like the garment makers in the play (heroine Esther creates sometimes elaborate underwear -the intimate apparel of the title- for other women, becoming a friend and confidante in the process), Linton weaves the discrete but exquisite strands of the production into a rich, tantalising whole. Each element (haunting sound, music and lights by George Dennis, Jai Morjaria and XANA respectively, period-specific designs by Alex Berry, subtly enhanced by Gino Ricardo Green’s video creations, as well as a flawless cast) works in harmony to create a couple of hours of taut, engaging, evocative theatre.

Nottage was inspired to write Intimate Apparel by the discovery of a photo of her great grandmother, a Barbadian seamstress who arrived alone in New York aged 18 to forge a life. Lynton and her designers frame each act and key moments with a striking freeze frame effect so that the living figures are briefly suspended in time like figures in an ancient photograph; when we enter the Donmar’s auditorium the individual objects (a bed, a trunk, the sewing machine upon which Esther whips up her creations) are labelled like exhibits in a museum. It’s a clever device, contextualising these vibrant characters while also humanising history.

Humanising history is of course the point of this rather marvellous play, or rather one of its many points. It’s also a love story of sorts but not between Esther (Samira Wiley) and George Armstrong (Kadiff Kirwan), the manual worker from the Panama Canal with whom she shares an epistolary romance before a disastrous marriage. It’s about Esther learning to love herself, finally…and about the love in friendship between women.

Wiley, previously seen on the London stage in Linton’s magnificent Blues For An Alabama Sky revival at the National and barely recognisable here, is deeply moving as a woman at odds with herself but possessed of a steely ambition (to open a ground-breaking beauty parlour for African American women) and a gift for empathy that she doesn’t even fully comprehend. It’s a beautiful performance, your heart actually aches for her, even though she’s too smart to ultimately be a victim.

Honestly though, all the other performances are up to this standard, it’s hard to know where to start with the superlatives. Kirwan has the most unsympathetic role but is thoroughly convincing as a man whose initial good intentions are scuppered by a combination of disappointment, emasculation and sheer bloody mindedness. Faith Omole is a like a firecracker tempered with a volatile but palpable humanity as the Tenderloin prostitute Esther is friendly with, and Nicola Hughes is lovely, funny but grounded, as the kind landlady with a past of her own. Claudia Jolly finds fascinating colours in the rich Upper East Side client whose affection for Esther spills over into unexpected territory. Alex Wldmann delivers a tender, compelling account of the Orthdox Jewish cloth merchant Esther has business dealings with but also a deep, complex connection.

This is one of those rare, blissful productions where everyone seems to be singing from the same metaphorical hymn sheet. I’m not sure Intimate Apparel as a script is right up there with the very best of Nottage’s work: there are a couple of coincidences and plot developments in the second half that slightly strain credulity but it’s also not hard to see why it has enjoyed multiple productions since its 2003 premiere. The dialogue is raw, honest and often painfully funny. It’s a powerfully women-driven story, touching, poetic, shot through with hard truth, and as compulsively watchable as a soap opera. Lynette Linton’s vivid, transporting production is the icing on a wonderful cake. A gem of an evening.