PIPPIN

Music and Lyrics by Stephen Schwartz

Book by Roger O. Hirson

Directed by Steven Dexter

Charing Cross Theatre – until 14 August

https://charingcrosstheatre.co.uk/theatre/pippin

Thanks to Broadway master showman Bob Fosse who directed and choreographed the legendary original production, Pippin was perceived for decades as a deathly commedia dell’arte carnival: a troupe of sinister but sexy players bring to anachronistic life the mythical story of Pépin, the wayward, questioning son of medieval emperor Charlemagne amidst flamboyant production numbers, lyrical ballads, clever patter songs and culminating in a bittersweet, unsettling finale.

Although there have been other takes on it, none of them really stuck until Diane (Waitress, Jagged Little Pill) Paulus’s rapturous 2013 New York revisal which turned the whole thing into a spectacular, slightly alarming circus. For this version, based on a smaller scale outdoor mid-pandemic mounting from last year, director Steven Dexter has gone right back to the show’s 1967 hippie roots (before Fosse got his splayed, angular hands on it) and the result is a couple of hours of whimsy and delight, albeit still with a certain amount of kick, that may surprise people who think they have a handle on Stephen Schwartz and Roger O. Hirson’s endlessly malleable show.

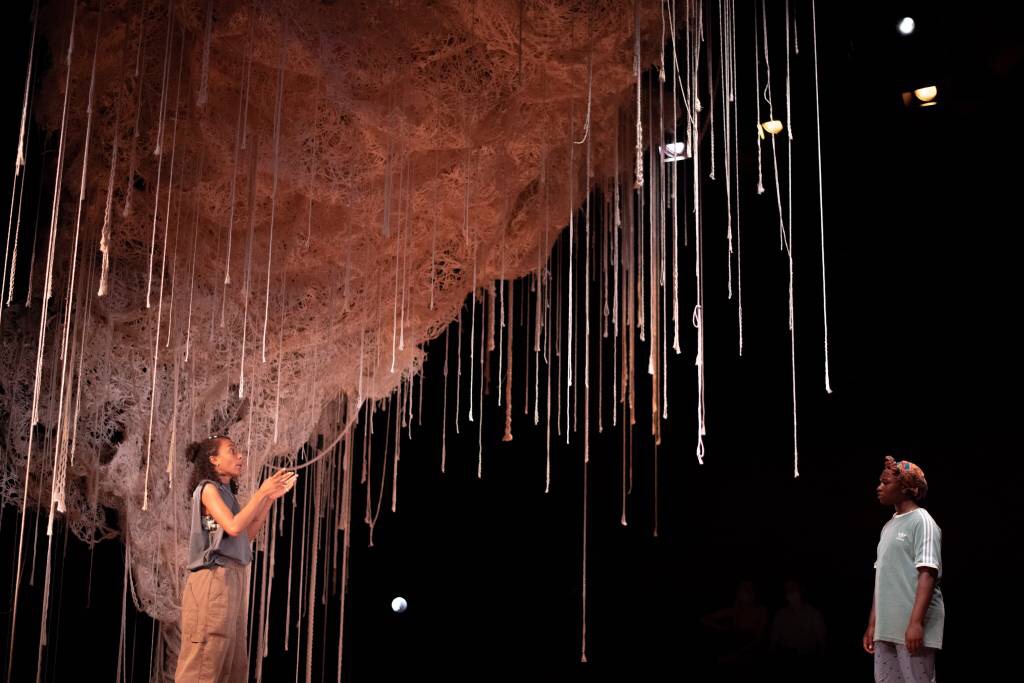

Wandering into Charing Cross Theatre’s traverse auditorium one could be forgiven for thinking we were about to be treated to an immersive revival of Hair when confronted with David Shields’s attractively chaotic set, and it’s fug of incense, rainbow tie-dyed sheets, hanging dream-catchers and abundance of dangling fairy lights. It’s like being at an outdoor festival during the Summer Of Love, yet ironically feels way more airy and atmospheric than when the earlier incarnation of this staging actually WAS outdoors, admittedly having to compete against the roaring traffic and street sounds of Vauxhall. There’s also real magic derived from Aaron J Dootson’s transformative lighting design.

Stephen Schwartz is the composer and lyricist of Wicked but Pippin is a more exciting and consistently melodic score. From the sparkle of the enchanting opening number ‘Magic To Do’ which introduces the players and the principal themes (“illusion, fantasy to study / battles, barbarous and bloody / romance, sex presented pastorally”) through an appetising, lilting mix of numbers esoteric and poppy (Pippin’s melodic cri de cœur ‘Corner Of The Sky’ was even a Jackson 5 hit in the 70s), this score is a gem. The lyrics have wit and, at times, surprising depth.

If Hirson’s book is less clear -who are these players that alternately cajole, torment or seduce the emotionally and spiritually lost hero? does Pippin really assassinate his warmongering father or is that just in his unsound mind?- it has heart and genuinely works as a sort of portentous but affable Flower Power romp.

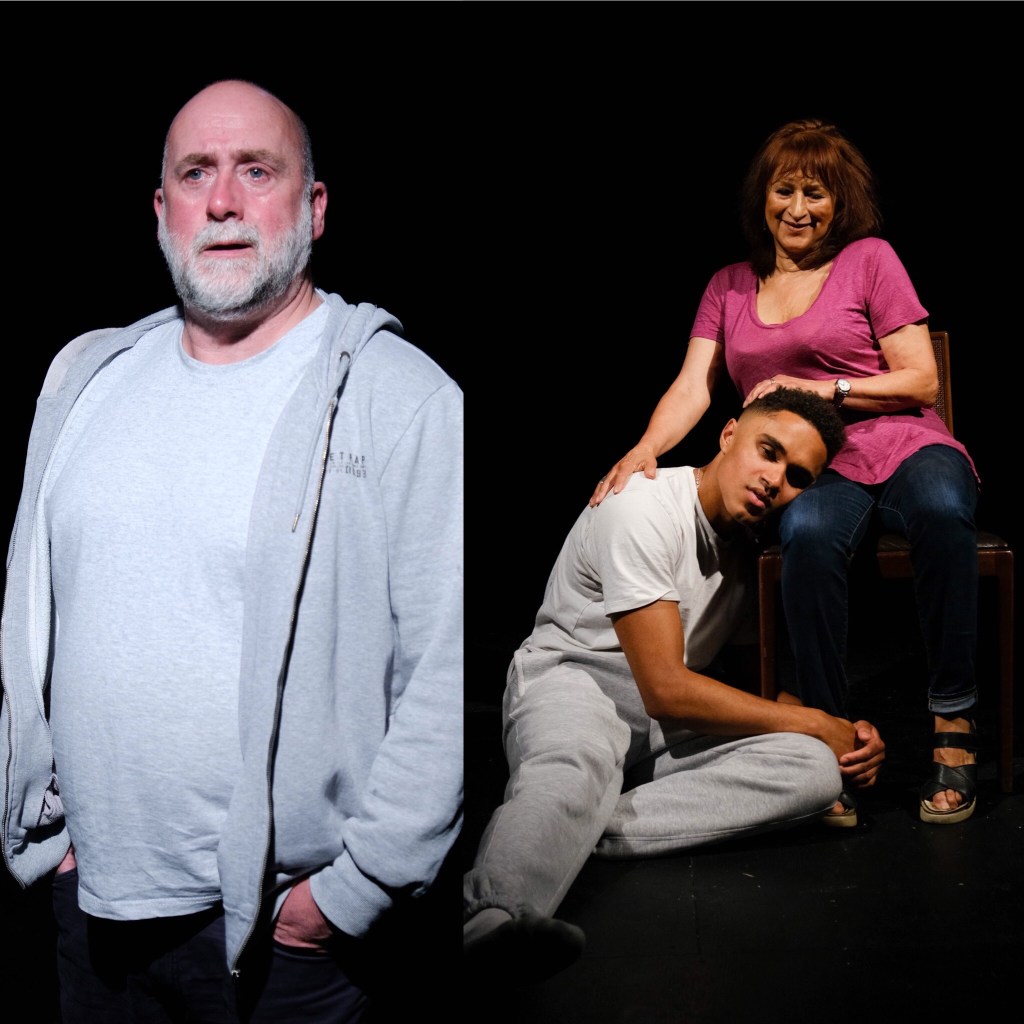

Ryan Anderson makes a wondrously athletic Pippin, and is likeable enough that the characters’s self-absorption isn’t a turn-off, and he negotiates the rangy demands of Schwartz’s wonderful but technically tricky songs with considerable panache. The Leading Player is the killer role though (in more ways than one) and has been performed by men and women. Here Ian Carlyle brings a breezy charm that curdles into something more troubling as the evening progresses. He moves like compressed liquid and sings up a storm, although the darker elements of the role could do with being amped up several notches: this Leading Player ends up feeling like a bully, but to really drive the piece he should be truly terrifying.

The three women in the company are flat-out stunning: Natalie McQueen brings a quirky manic energy but innate goodness to Catherine, the young widow Pippin takes up with, and makes something genuinely moving out of her exquisitely sung closing solo. Gabrielle Lewis-Dodson is a knockout as the hero’s ambitious, morally bankrupt step-mother, all flash, sass but dead-eyed stare. Genevieve Nicole, a thrilling, peerless Leading Player in Jonathan O’Boyle’s acclaimed Hope Mill and Southwark Playhouse version a few years back, comes close to stopping this show as Pippin’s rapacious-for-life grandmother, with the joyous but regret-tinged singalong number ‘No Time At All’. This role, like most of the others in the show, is open to a number of interpretations, but here Nicole conceives her as a sort of Park Avenue Grande Dame transplanted to rural hippiedom and living her best life, and the result is breathtakingly funny.

As Pippin’s father, step-brother and step-son respectively, Dan Krikler, Alex James-Hatton and Jaydon Vijn may have less to work with but prove terrific triple threats. Nick Winston’s choreography, unusually for a production of Pippin, feels more reminiscent of the long-limbed elegance of Gillian Lynne’s jazz-ballet fusions than Fosse’s more jagged work, but it’s consistently exhilarating.

The juxtaposition of showbiz razzle dazzle with existential despair that makes Pippin such a unique and compelling addition to the musical theatre canon is given shorter shrift than in other version I’ve seen but maybe after the sixteen months we’ve all had, this sunnier, sweeter interpretation is all we can cope with right now. It’s a shame also that the transformation at the end (no spoilers, go see it) isn’t more extreme. Still, even if it’s not as emotionally satisfying as it could be, this Pippin is still cracking entertainment.