BROKEN LAD

by Robin Hooper

Directed by Richard Speir

Arcola Theatre/Arcola Outside – until 6 November

https://www.arcolatheatre.com/whats-on/broken-lad/

Kudos to the Arcola for finding a solution to the ongoing Covid situation by moving their entire performance operation to the outdoors for the time being. Arcola Outside has the same rough-and-ready charm as the adjacent main building, a decent sized stage, and an attractive, well-stocked bar, but with lots of air flow and plenty of room for social distancing. I guess there’s not much to be done about the amount of din coming from nearby Dalston Junction but one would hope that they’re planning to implement some sort of heating as the winter comes on, as it could get uncomfortably cold when the weather turns.

Plummeting temperatures or not, patrons planning to experience the first new play presented in this space may feel the need to take heavy advantage of that aforementioned well-stocked bar. Unfortunately, Robin Hooper’s so-called comedy is a bit of a stinker, a whiney, misogynistic dirge that would have seemed a bit dated in the 1980s but manages to look simultaneously offensive and aimless when viewed through the prism of 2021 sensibilities.

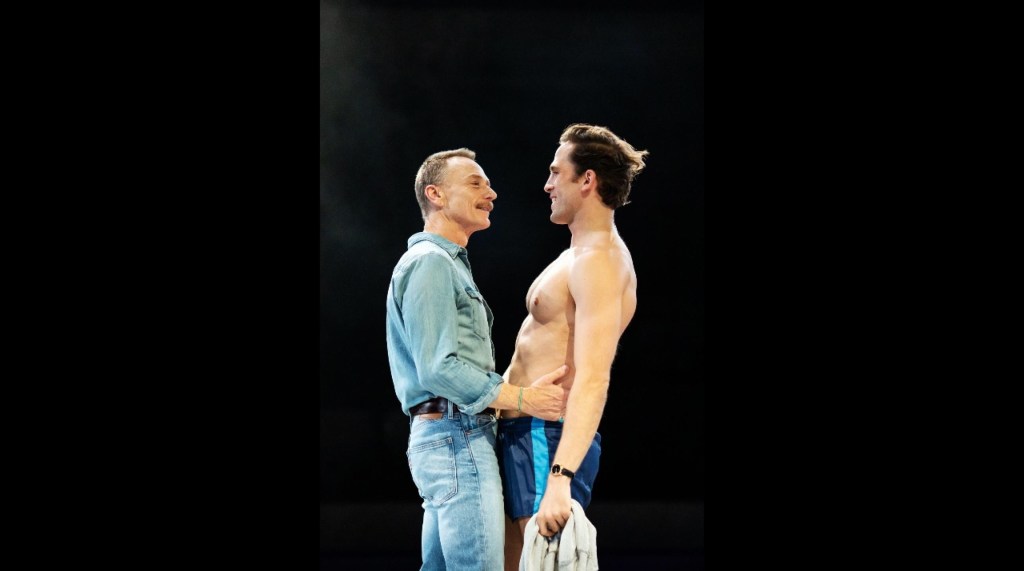

Comedian Phil, in a game performance by Patrick Brennan, was once a stalwart of primetime TV but is now reduced to gigging in rundown pubs. As he readies himself for his hopeless next set, his assistant-cum-manager Ned, an unhelpful variation on the “lonely old homosexual” trope, looks on – when he can tear himself away from the gay dating apps – with an unlikely combination of support and lust (yep, he has long held a torch for the unappealing Phil, which makes no sense at all until he also reveals that his celebrity crush is one Boris Johnson, so…yeah…his taste in men is unconventional, to say the least).

Also circling are Phil’s sulky son Josh (Dave Perry, doing a lot of pouting and staring) who’s trying to work out if the old man has bonked his shrill girlfriend (he has), and, inexplicably, Phil’s sourly disapproving ex-wife (Carolyn Backhouse, doing her best in a thankless role). I can’t remember the last time I saw a play where none of the characters had a single redeeming feature, and Hooper’s script is sketchy on whether or not Phil is even any good as a comic. Certainly, the bit of his act that we get to see (through an upstage window, which is plenty near enough, to be honest) is borderline obscene and about as funny as a flag at half mast, while his offstage shtick consists mainly of warming over end-of-the-pier gags that weren’t particularly amusing even back in the ‘70s.

Even more mystifying is the sexual thrall Phil seems to hold a couple of the other characters in. Maybe Hooper was trying to create an English Lenny Bruce or a modern variant on John Osborne’s Jimmy Porter, but what we get is a wheedling loser with bucket loads of self pity and a decidedly dodgy take on gender politics: apart from the divorce, his biggest problem with his ex seems to be that she was a successful businesswoman who was financially independent of him. This low level misogyny extends through the script to Josh’s girlfriend Ria (Yasmin Paige) who had been a fan of Phil’s when she was a teenager (er…why?) and is now also an incest survivor who slips into bed with both the comedian and his ghastly son. All this doesn’t so much stretch credulity as strangle it, especially during the melodramatic confrontations, and there is never a satisfactory reason for us to care about the fate of any of these unsympathetic individuals.

Richard Speir’s staging is big on pacing about but lacks pretty much any subtlety, a problem exacerbated by the open nature of the space, where all the outside noise requires all actors to be mic-ed up, although when the script is like this I’m not sure that catching every line is really doing anybody any favours. All in all, this is a depressing evening, one that wastes the talents of some fine actors, and it’s a rare misstep in the Arcola’s usually superb programming. I suppose it could be argued that Jim Davidson’s recent TV embarrassment lends this unpleasant piece a certain topicality with it’s theme of reactionary, past-it comedians getting their comeuppance. The best thing I can say about is that it only lasts 90 minutes. Feels a lot longer.