THE HUMAN VOICE

by Jean Cocteau

Adapted and directed by Ivo van Hove

Harold Pinter Theatre – until 9 April

https://thehumanvoiceplay.co.uk/

This is one tough sit.

I wonder if this production was conceived during the first lockdown. A Jean Cocteau monologue for a woman unravelling on the phone while her lover leaves her might have felt like a good idea at a time when solo shows seemed the only way forward for live theatre. Plus we were so grateful to see anything that wasn’t on a screen, let alone the work of an internationally acclaimed director and an award-winning leading actress, that the fact that the central protagonist is a privileged, humourless, self-indulgent whiner maybe didn’t seem like so much of an issue. Unfortunately, in 2022, this obscure confection looks a bit odd in an increasingly diverse theatre landscape where people have long started to talk to each other again, and we prefer our live entertainment to either provide pure escapism or connect us to a more profound understanding of the world at large. This does neither. It also whiffs unappealingly of misogyny (she can’t be with the man she wants and has so little agency that she bombards him with phone calls, then contemplates suicide).

Ruth Wilson and director Ivo van Hove worked together on the National Theatre’s 2016 Hedda Gabler so presumably have some sort of artistic simpatico plus, given their worldwide success and acclaim, have professional commitments booked up for years in advance. Therefore it’s undoubtedly something of a scheduling triumph that they are available to finally give us this three week West End season. Whether or not it’s worth their, or our, time and effort is entirely another matter. Seventy minutes has seldom passed so interminably: it feels more like three hours.

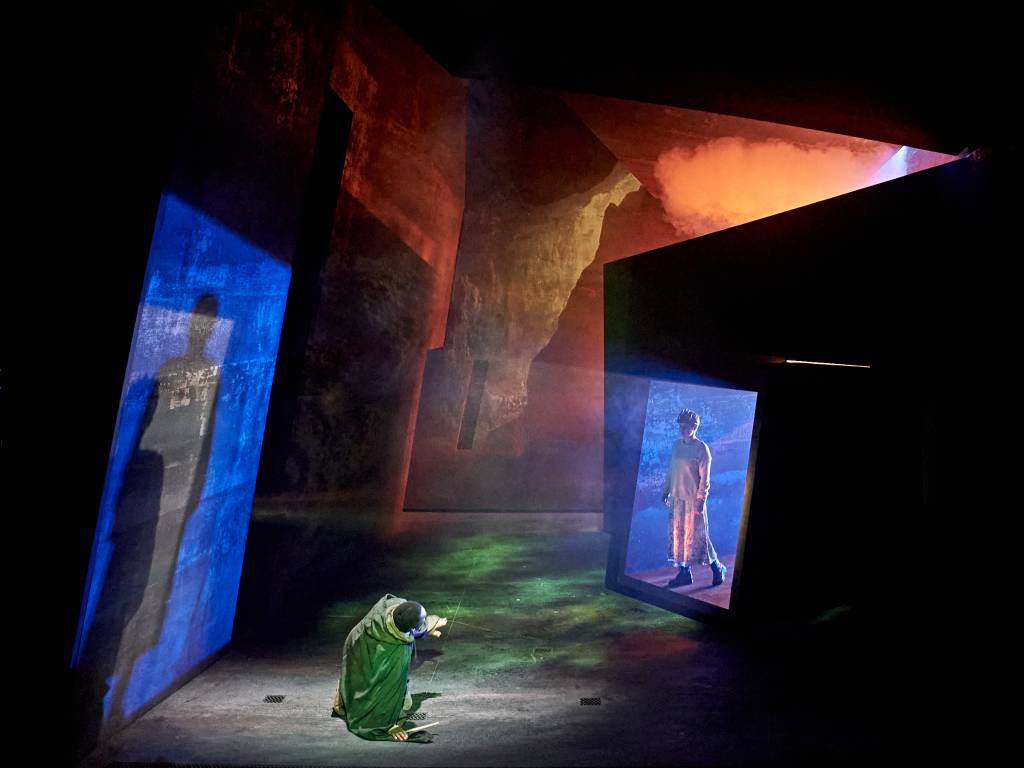

Cocteau’s text is riddled with ambiguities, at times it seems possible that the departing lover on the other end of the phone might be a figment of the woman’s imagination, and the conflicting voices that periodically come through on crossed lines are all in her head. There is little elucidation, or humour. Longtime van Hove collaborator Jan Versweyveld’s chilly perspex box set keeps us at a further remove (Wilson is mostly viewed from the knees up behind a see-through screen, when she isn’t crawling about on the floor pretending to be a dog, or, in one particularly interminable section, sprawled motionless against a wall like a broken doll, facing away from us for the entire duration of a song.)

As a study in masochistic boredom and isolated despair, the piece carries a certain conviction and at least the leading lady here manages to avoid having unidentified liquid substances dripped on her (a van Hove motif that was thrillingly effective in his mould-breaking A View From The Bridge at the Young Vic but became eye-rollingly familiar thereafter). Wilson is technically proficient throughout but cannot disguise the dreary one-notedness of what she’s required to do, her performance only catching fire in a couple of welcome moments of white hot fury.

The lighting and sound elements are impressive (there is an almost constant thrum of popular music, from Radiohead to Beyoncé, as though to exacerbate the heroine’s loneliness and misery) but the central conceit of crossed telephone lines doesn’t really work in this production’s ultra-modern milieu. The timing feels out in other ways as well: it would be hard to elicit much sympathy for this self-absorbed central character at the best of times, but at this particular point in human history, the whole experience proves barely tolerable.

This is one for Wilson fans, van Hove connoisseurs and Cocteau completists (surely there are some?) only. I came away mostly thinking, bloody hell no wonder he dumped her. The emperor’s new clothes are looking distinctly threadbare.