THE SOUND OF MUSIC

Music by Richard Rodgers

Lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II

Book by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse

Directed by Adam Penford

Chichester Festival Theatre, Chichester – until 3 September 2023

https://www.cft.org.uk/events/the-sound-of-music

Aside from The King And I and Yul Brynner’s indelible flawed monarch on screen, on Broadway originally and in countless international revivals, nothing else in the Rodgers and Hammerstein canon of classic musicals is as inextricably tied to one star performer as The Sound of Music. Julie Andrews never played Maria Von Trapp on stage (the show and role were created for American showbiz sweetheart Mary Martin, who had previously starred in the same team’s South Pacific) but mention The Sound of Music and the first image in most people’s minds will be of the youthful Julie in the film version, arms outstretched and hands splayed, twirling ecstatically atop an Alp as she soars through the rapturous title song. It’s a long shadow to escape from, and Adam Penford’s captivating new production at Chichester simultaneously celebrates that popular vision of this beloved property while also throwing up a few surprises of its own.

Most stage revivals tend to incorporate the changes and additions made for the movie (the inclusion of “I Have Confidence”, written specifically for Andrews in the film, the iconic “My Favourite Things” as a mood lifter for the frightened Von Trapp children during a thunderstorm, “The Lonely Goatherd” presented as a puppet show by the kids to impress Elsa, their potential new stepmum…). This version however goes back to the first 1959 stage iteration, honouring the original (and meticulously crafted) book by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crowse, and the result is a show more sophisticated, less sugary sweet and altogether more dramatic than I remembered.

Back in are “How Can Love Survive” and “No Way To Stop It”, the tart, cynical duets for Elsa and her friend Max, the former dealing with financial expediency versus romance, and the latter with the rise of Nazism, while “My Favourite Things” is, as in the original, a duet at the top of the show for the Mother Abbess (Janis Kelly, exquisite) and Maria, and the yodel-happy goatherd number is returned to its positioning as the children’s storm distraction, complete with joyous, thigh-slapping choreography by Lizzi Gee. The London Palladium version that followed the game-changing BBC How Do You Solve A Problem Like Maria? TV casting contest tried to meld together elements of the Broadway original with the movie version and resulted in something messy and unfocused, if enjoyable. This is infinitely more satisfying.

Penford and team aren’t trying for a wholesale reinvention like the current Daniel Fish Oklahoma!; it’s not even as much of a rethink as Daniel Evans’s terrific South Pacific for this venue a couple of years ago, with which it shares a leading lady, the luminescent Gina Beck (and more on her in a moment…) but a rare chance to see the piece as first written rather than mashing up the original work with the film. This is still the same sentimental, open-hearted, family friendly creation that has delighted musical lovers for generations: the songs continue to transport and bring a lump to the throat, the kids are still adorable; but the shadows are fractionally darker and the emotional ante is a little more elevated.

I suspect the main reason for this is that it is, for the most part, superbly acted. Edward Harrison’s Captain has a heartbreaking, borderline disturbing, detachment and edge of darkness borne of genuine loss: watching him respond to hearing his children sing for the first time is deeply moving. The Elsa of Emma Williams is more warm and likeable than usual, she’s not just some snooty sophisticate trying to drive a wedge between a man and his inconvenient kids, but a fully rounded woman who cares very deeply about her possible new family yet is acutely aware she is like a fish out of water; some of her martini-dry line readings are extremely funny, and humanising her makes the unspoken contest between her and the adored Maria all the more fascinating.

Lauren Conroy invests older daughter Liesl with intelligence and a subtle toughness that is miles away from the saccharine portrayals of yore, suggesting the pain of a young woman who unwillingly has had to be many things to many people following the death of her mother. Opposite her, Dylan Mason’s delivery boy Rolf is ardent and graceful, then convincingly undergoes a chilling transformation before a final moment of tormented nobility. Opera star Janis Kelly suggests a real woman underneath the Mother Abbess’s robes and rightfully brings the house down with the legendary “Climb Every Mountain”.

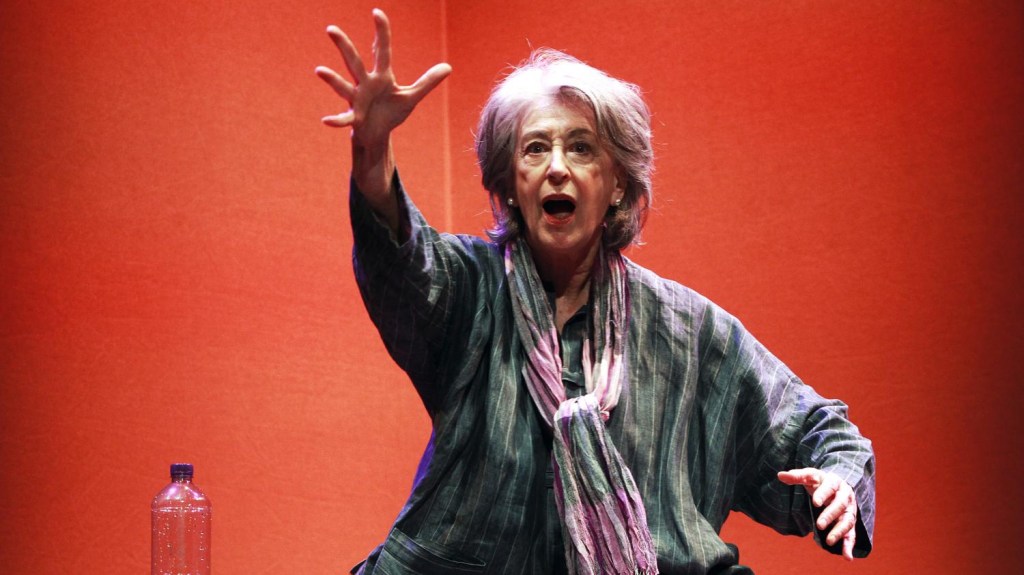

The beating heart of the production though is Gina Beck’s Maria, a creation of such magnetism, musicality, emotional depth and irrepressible good humour that she almost succeeds in obliterating memories of most previous interpreters of the role. Whether standing up to the Captain in defence of his children, befriending the lovelorn Liesl, or engineering the family escape from the impending threat of the Nazis, she’s strong, centred and entirely credible. Her rapport with the kids feels genuine, her deadpan comedy is pretty wondrous and she makes something deeply affecting out of Maria’s crisis over her feelings for Von Trapp versus her commitment to God. She’s sunny but rock solid, the kind of woman you would always want on your side. Her acting is so vivid and her singing so organically tied to her character choices that it is almost a surprise when she suddenly produces fearless, crystalline top notes….but it’s an exhilarating surprise, or rather a reminder that she’s played several classic soprano roles, including Christine Daaé, Wicked’s Glinda and as an entrancing Magnolia in Daniel Evan’s flawless Sheffield then West End Showboat. Beck’s Maria is so breathtakingly fresh that it feels a shame that the design team decided to give her a wig, admittedly a very convincing one, that recalls Andrews’s hair from the film. It inevitably invites unhelpful comparisons and is a rare misstep in a production that otherwise gets so much right.

Musical supervisor Gareth Valentine’s fourteen piece band occasionally lack the orchestral sweep that this score ideally needs, but for the most part wrap Rodger’s famed melodies in the glint and sparkle of a mountain stream, and the choral singing from the fine company of female voices (the nuns!) is absolutely gorgeous. No stage production can realistically expect to replicate the astonishing Alpine vistas of the movie, but Robert Jones’s handsome granite-like sets have a sculptural quality that works beautifully, especially when atmospherically lit by Johanna Town, and some of the interiors that swing on and off are attractive and opulent. The overall visual impression of the production is perhaps darker than one might have expected, but it feels lush and dramatic.

All in all, The Sound of Music isn’t perhaps the strongest in the R&H portfolio: South Pacific is probably more intelligent, Carousel more emotionally resonant and Oklahoma! more vibrant, it has moments of irredeemable tweeness, and some of Hammerstein’s lyrics sacrifice clarity and concision to syrupy mawkishness: “like a lark who is learning to pray”?! Nevertheless it remains a fine example of musical theatre from the Golden Age of Broadway. This is a truly lovely production of it, and Ms Beck reconfirms her position as one of this country’s most irresistible musical theatre leading ladies. Well worth the trip to the South Downs.