NYE

by Tim Price

Directed by Rufus Norris

National Theatre/Olivier, London – until 11 May 2024

https://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/productions/nye/

then Wales Millennium Centre, Cardiff – 18 May to 1 June 2024

https://www.wmc.org.uk/en/whats-on/2024/nye

The National Theatre and the Wales Millennium Centre collaborating on a stage life of Aneurin Bevan, the fiery Welsh politician central to the setting up of the NHS, seems like a marriage made in theatrical heaven. There are indeed moments where Tim Price’s script and Rufus Norris’s showy, shouty production achieve true greatness, but they are tempered by too many sequences and choices that prove bewildering rather than brilliant.

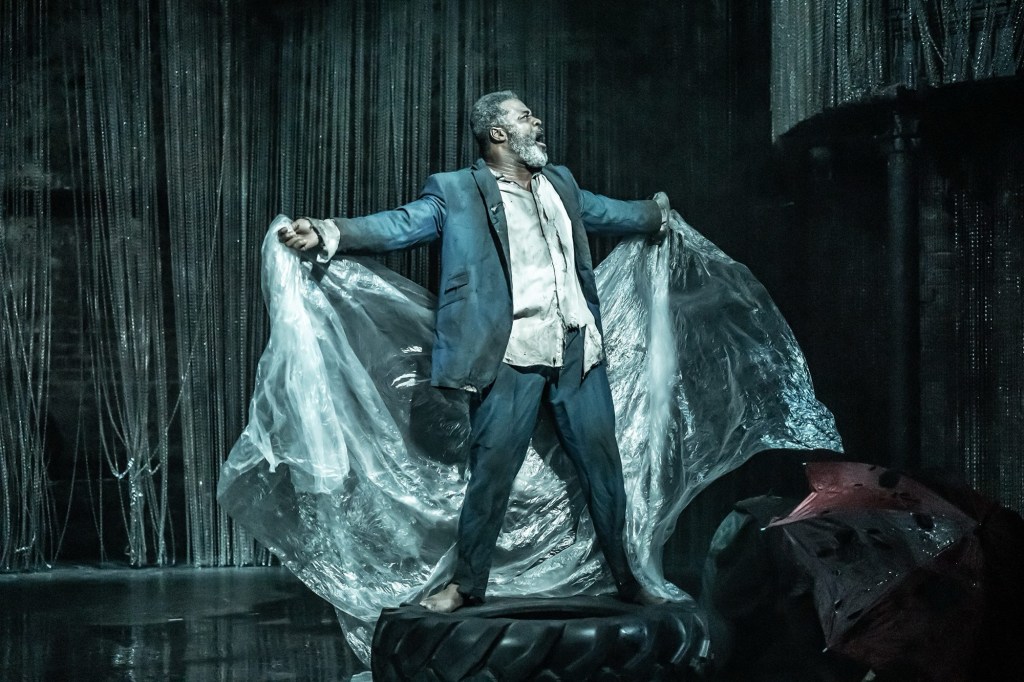

As the story is told in flashback from Bevan’s death bed in one of the hospitals helped to fund and revitalise, Michael Sheen’s Nye (short for Aneurin) spends the entire show in pyjamas. In a similar vein, Vicki Mortimer’s spare, wide set, which, like much of the blocking of the actors, looks better suited to the more traditional playing area of Cardiff’s premiere house than the open stage of the Olivier, is informed by the green, draw-along curtains of hospital wards, at one point configuring at different levels to create an approximation to the interior of the House of Commons.

That striking image aside, the look of the production is austere, ugly even, with a reliance on projections that often sees the hard-working Sheen bellowing at gigantic monochrome pre-recorded figures. Office desks caper around like bumper cars, hospital beds tilt and spin, actors perform Steven Hoggett and Jess Williams’s cumbersome choreography, all adding to an overall impression of Nye being more of a pageant than a play, especially given the sketchiness of the characterisations. Many of the people seem more like figures in a cartoon than fully fleshed out human beings.

There’s even a full scale production number, where Sheen (in excellent voice) leads the company in a rousing but bizarre rendition of the Judy Garland classic ‘Get Happy’. I’m all for inserting big numbers into plays (Stranger Things The First Shadow has one that is an absolute stunner) but this feels unnecessary, and a little like it’s trivialising something as important as the inauguration of the National Health Service. When not providing an incidental chorus line, the supporting cast also pop up as a series of Kafka-esque politicians and even a rugby scrum, which isn’t inappropriate given the Welsh setting.

There’s a cloying vein of sentimentality in Price’s writing (“I’ll take care of all of you” cries Nye into the void as he cradles his miner father who’s expiring of black lung disease, and the staging of Bevan’s own death is staged with such over-choreographed portentousness that it robs the moment of authentic emotional power) and the gear changes in tone and emphasis never feel smooth. The razzmatazz sits uneasily alongside the cold, hard information, such as the fact that only four thousand doctors originally voted to work in the NHS against the forty thousand who didn’t.

Nye is at its most stirring, persuasive and indeed timely when the principal character is expounding on the importance of free health care for all. Sheen brilliantly captures the passionate orator and the eccentric egotism that seem to have characterised Bevan. The play also serves as a timely reminder that well behaved people don’t necessarily achieve as much as their more disruptive counterparts, and suggests that Bevan’s commitment to the greater good was at least in part to his failure to step up for his immediate family (Kezrena James finds real power in his disappointed sister’s admonishments, and doubles nicely as a kindly nurse awestruck at her high profile patient). This Nye is wayward, charming and often exasperating. Sharon Small is sharp but warm as his life partner Jennie Lee who put her own political ambitions aside to support Bevan, and Roger Evans is equally fine as Archie Lush, the childhood friend who became a lifetime constant.

Most of the rest of the acting is bold and non-specific, not surprising since the majority of the cast are given mere sketches and caricatures to work with. Tony Jayawardena’s uncanny Winston Churchill is a notable and impressive exception to this though, cutting a familiar figure but so multi-faceted and playful that it transcends impersonation. There’s also a delightful irony in having an actor of global majority heritage playing a well documented racist. Jayawardena gives him more charm than he probably deserves.

Sheen’s magnetic central performance holds the whole unwieldy piece together, and finds an energy and focus that compels, despite the sometimes uninspired writing. Judged as a play, Nye is, in all honesty, a bit of a mess and Norris’s overlong staging, although often inventive, doesn’t make it all coalesce, but the energy of the cast and the sheer potency of the themes ensure that it still packs a punch.