THE WIZ

Book by William F Brown

Music and lyrics by Charlie Smalls

Additional material for this production by Amber Ruffin

Directed by Schele Williams

Marquis Theatre, New York City – until 18 August 2024

Featuring a reworked book by TV writer and comedian Amber Ruffin and dances by Beyoncé’s choreographer of choice JaQuel Knight, that owe more to Hip-hop, Dancehall and Urban Ballroom than traditional Broadway, this is less a revival than an all-out revisal of the beloved Charlie Smalls-William F Brown property. The Wiz was always a triumph of exuberance and bravura belting over craft anyway, albeit one that ran for more than 1600 performances in its original Main Stem iteration, so an attempt to drag it kicking and screaming into the 21st century is unlikely to have purists bellowing from the rooftops with outrage.

They may be disappointed at the excision of Toto (losing a dog in real life is always a terrible idea but, as the recent London Palladium Wizard of Oz proved, having a puppeteer onstage throughout to evoke one à la War Horse can be an unwelcome distraction) and surprised at heroine Dorothy’s new back story: she’s now an urban youngster adrift in a rural landscape following her mother’s death, bullied by local kids and trying to make a new life with her Aunt Em. Her grief and isolation isn’t belaboured but it lends a raw, streetwise edge to newcomer Nichelle Lewis’s interpretation of the role that genuinely ups the emotional ante in a show that otherwise comes at you like a garishly coloured, hi-energy juggernaut of camp and go-for-broke enthusiasm.

Lewis is a real find; this Dorothy is clear-eyed, sincere but no pushover, and she makes something passionate and affecting out of the much covered soul ballad ‘Home’ that brings the show to a stirring, if somewhat abrupt, ending. Director Schele Williams has surrounded her with quality. It’s hard to imagine a more engaging central quartet than Lewis, Avery Wilson (as an athletic, über-camp scarecrow barely a z-snap away from RuPaul’s Drag Race), Phillip Johnson Richardson (an adorable Tinman with a sweet soul voice and a surprising amount of emotional depth) and Kyle Ramar Freeman’s hilarious, scenery-chewing sweetie of a Lion (“y’all are obsessed with me!” he squeals at his new friends, and frankly who could blame them for being). High octane and far-fetched it may all be, but these young performers, short on Broadway credits as yet but big on authentic star quality, make rooting for them entirely essential.

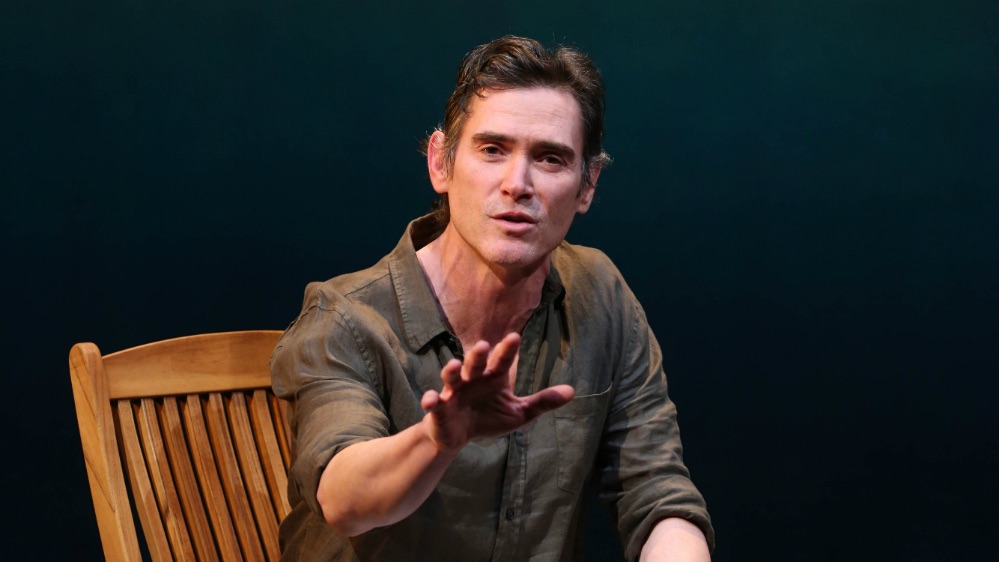

Then there’s clarion-voiced Melody A Betts in a fiery, funny double role of Aunt Em and a vicious yet strangely endearing Evillene. Allyson Kaye Daniel is fabulous but criminally underused as one of the good witches, while recording star Deborah Cox, all blonde curls and elaborate riffing, is fine but a trifle underpowered as Glinda. The other lead with marquee name recognition is Wayne Brady in the title role and he brings buckets of slippery charm and magnetism, and gets to bust out some pretty impressive moves. The ensemble work is terrific, even when given some less-than-inspired things to do, such as the interpretative dance of the hurricane that whisks Dorothy off to Oz (it may be an homage to the original but it’s still naff) or the slightly toe-curling business for the yellow brick road made flesh, clad in what look like saffron coloured beefeater outfits.

Those aberrations aside, Knight’s choreography is exciting, bringing a new dance language to Broadway. The voguing-heavy Emerald City ballet that opens the second half is pure exhilaration, full of attitude and limb-popping joie de vivre, whipping an already up-for-it audience into total frenzy. Williams’s direction is more serviceable than distinctive with a couple of disappointing key moments, such as the melting of Evillene which is staged with minimum panache but maximum volume. Still, she finds the comedy (although it’s not hard to locate thanks to Ruffin’s zinger-soaked new script) and, crucially, the heart in this crowd pleaser.

The production’s touring routes are evident in the super-busy video-generated backdrops and slightly wobbly set pieces (courtesy of Daniel Brodie and Hannah Beachler respectively) but that matters surprisingly little thanks to the raw talent out front, and the show is never unappealing to look at. Jon Weston’s sound design isn’t always as clear as it could be.

Joseph Joubert’s band is large by current Broadway standards and sounds brassy, funky and fine. ‘Ease On Down The Road’ ‘No Bad News’ and others pop and sparkle, even if there’s sometimes a feeling that the performances are more remarkable than the actual material. That’s not true though of the anthemic, celebratory ‘Brand New Day’ that follows the demise of the wicked witch…good luck with getting that unique syncopation and soaring melody out of your head for days after watching the show.

In a Broadway season that includes the triumphant resurrection of Merrily We Roll Along, the import of the London Cabaret at the Kit Kat Club and the critically hallowed new version of The Who’s Tommy, this imperfect but uplifting revival of an imperfect but uplifting musical is unlikely to get much love from the Tony awards (although I’d be thrilled to see some of the performances honoured). I’m not sure that even matters: it’s got title recognition, it’s family friendly and this is the first time The Wiz has been on Broadway in forty years, so it feels like an inevitable hit. There are many valid, impressive and searing instances of Black misery and trauma in the theatrical canon, and it’s just lovely to experience a show that simply espouses Black joy. This “brand new day” may not really be all that new, but it surely is a blast.