The Who’s TOMMY

Music and lyrics by Pete Townshend

Book by Pete Townshend and Des McAnuff

Additional music by John Entwistle and Sonny Boy Williamson II

Directed by Des McAnuff

Nederlander Theatre, New York City – open-ended run

Can the same director reinvent a beloved show more than once? On the basis of this crowd-pleasing revival of The Who’s Tommy, returning to Broadway by way of Chicago’s Goodman Theatre and once again staged by Des McAnuff who won the 1993 Tony for his previous version of the legendary rock opera, the answer is an emphatic, if slightly qualified, yes.

The world has changed considerably in the 30+ years since McAnuff’s mind-blowing original vision of The Who’s rock rollercoaster first exploded onto Broadway (it transferred to the West End’s Shaftesbury Theatre for a years run in 1996 with a cast that included Kim Wilde and a young Nigel Harman) and certain elements of this tall tale of “that deaf, dumb and blind kid [who] sure plays a mean pinball” have not aged well. Those lyrics from the most famous number (‘Pinball Wizard’, which once again brings the first act to a thunderous, thrilling conclusion, with go-for-broke choreography by Lorin Latarro, who is fast turning into one of New York’s preeminent dance directors) are a major indication as to what has altered.

Looked at through a 21st century lens, Tommy appears uncomfortably ableist. The titular character’s instantaneous descent into silence and blindness (apart from staring into a mirror) after witnessing his father murder his mother’s lover, may be intended as symbolic but it now seems as insensitive as it’s poignant. Furthermore, the young Tommy, unprotected by his senses, is thrown around like a rag doll, sexually abused by his uncle (John Ambrosino) in a terrifyingly intense sequence that’s thankfully at least not graphic, before being assaulted by a prostitute (Christina Sajou’s extravagantly feral Acid Queen) in a misguided attempt to “cure” him.

While I would defend to the death the right of popular entertainment to explore and confront some of the more disturbing facts of life, Tommy, in 2024, feels like an outlandish special effects fest and collage of (admittedly fabulous) music, and these darker aspects tend to register as jarringly exploitative, sensationalist add-ons to a fantastical narrative. Die-hard fans may not care, but newcomers may find the more unpalatable aspects of the story pretty hard to take, especially when they’re presented with minimum illumination or explanation but maximum razzle dazzle.

Furthermore, the principal characters Mrs Walker (Alison Luff) and Captain Walker (Adam Jacobs), Tommy’s parents, school bully Cousin Kevin (Bobby Conte) and Tommy himself (Ali Louis Bourzgui) aren’t nuanced enough to penetrate through the flash and spectacle of the staging and seem more like archetypes than flesh and blood people, which is no fault of the excellent performers but more that the bells and whistles of McAnuff’s vision and the sheer, roof-shaking bombast of this mostly enthralling score don’t allow for much in the way of humanity.

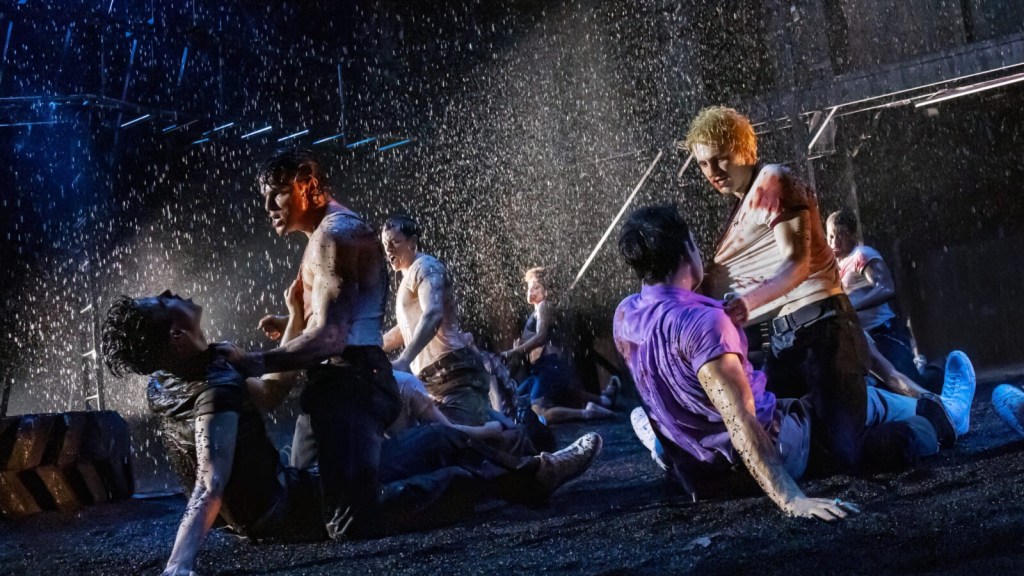

All that said, there’s still a heck of a lot here to like: Latarro’s choreography, dynamically mixing up styles and moods, is absolutely terrific, and performed with precision and glorious energy by a crack ensemble, who also sing like dreams. Tommy feels nearer to a dance show now than it ever did previously, and that’s possibly the only area where this version improves upon its predecessor.

All the voices are wonderful, although Bourzgui’s Tommy was struggling with the higher notes at the performance I attended. Probably best to draw a veil over the attempts at British accents (the majority of the show is set in London during and after WW2) and just enjoy the uplifting spectacle and musical excitement. Conte displays commanding stage presence as the bullying Kevin, and Luff and Jacobs inject their roles with more purpose and feeling than are in the writing. Luff’s voice in particular is a thing of wonder and when she cuts loose in Mrs Walker’s angry rock tirade ‘Smash The Mirror’ she’s like a severed power cable. Bourzgui’s Tommy has undoubted charisma but feels diminished by the decision to turn him from a messianic cult figure to effectively a social media influencer.

All kudos to McAnuff for not simply rehashing the work that won him accolades thirty years ago. This new Tommy is genuinely reconceived, and in some ways, for all technical ingenuity of Peter Nigrini’s projections, Amanda Zieve’s lighting and above all Gareth Owen’s truly awesome sound design, feels less hi-tech at times than the previous production: human figures and inanimate objects are borne aloft and spun through the air by black-clad figures, kuroko-style. Nigrini’s work and David Zinn’s gleaming settings favour a black and white pallet with occasional flashes of acidic yellow; the whole thing moves with an oil slick smoothness.

Those of us who were knocked sideways by the earlier iteration of The Who’s Tommy, whether here on Broadway, in the West End or during its extensive North American tour, might experience a certain sense of anticlimax though. This new version undoubtedly achieves lift-off some of the time when it needs to, but overall feels less urgent, less sensorily overwhelming, less epic, with the result that the lameness of much of the storytelling, the absence of humour and the random nature of some of the character motivations are left more obviously exposed. McAnuff’s new concept of setting part of it in the future doesn’t entirely work since there is little correlation between that and the core story.

This new Tommy is unquestionably a big, flashy Broadway night out. The music remains hugely exciting, and when the stellar vocals, athletic dancing, and visual effects coalesce it provides maximum musical theatre uplift. It’s just that in a season that includes stunners like Hell’s Kitchen, The Outsiders and the import from London of Cabaret, this melodically profligate, dramatically undernourished throwback feels a bit lacking. It’s certainly an enjoyable journey, but not an entirely amazing one.